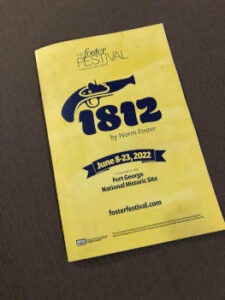

1812 at the Foster Festival

While you and I were spending the pandemic hunkered down, trying to figure out what to watch next on Netflix or any of a dozen other streaming services, Norm Foster was busy banging out 10 plays. That’s how you become Canada’s most prolific playwright. One of them, the tersely titled 1812, is receiving its world premiere in a charming little outdoor theatre on the grounds of the Fort George National Historic Site in Niagara-on-the-Lake. (A reading of 1812 was presented digitally in 2021.) The production marks the reemergence of the Foster Festival from a two-year, Covid-mandated hibernation.

The choice of venue is fitting since the play is set during the War of 1812, in the course of which Ft. George was destroyed by those nasty Americans. The geographical setting of 1812, the play, however, is along the Maine/New Brunswick border where the Canadian town of St. Stephen and the American town of Calais face each other across the narrow St. Croix River. The two towns lived in perfect harmony until the declaration of war reached them. Even then, it seems to have taken some time for the folks on either bank of the river to take it seriously. And even when they did, they proved to be less than vicious adversaries.

No less an authority on Canadian history than Mike Myers assures me that Canada won the War of 1812. I’d had the vague impression that the United States emerged victorious, but then I spent some of my formative years in an English boarding school so my knowledge of American history is sketchy at best. Fortunately, a degree in history is not a prerequisite for enjoying this show.

Foster took his inspiration from an apparently true story of how, when hostilities were in full force, the Canadian mayor lent his American counterpart a cache of gunpowder so the Yanks could celebrate July the Fourth. That incident plays a relatively minor role in 1812, which focuses its attention on the romantic entanglements of the Edwards family and the problems created by divided loyalties brought to the surface by a war in which no one particularly wants to be involved.

The portly Wallace Edwards (David Nairn) is a hale-fellow-well-met sort of man, which no doubt explains why he is considered the mayor of St. Stephen, even though the post does not officially exist. His long-suffering wife, Millicent (Patricia Yeatman) patiently deals with his mild cognitive impairment, the result of a fall from a horse. Their comely daughter Caroline (Ellen Denny) is a strong woman capable of shoeing a horse and riding the most fractious steeds.

Caroline has a suitor, Frederick Thomas (Jesse Dwyer), a college graduate reduced to using his math skills in his father’s tailoring business. He hails from American Calais. But Caroline is more taken with Ben Strong (Edmond Clark), a British immigrant to Calais, whose sturdy good looks and rich baritone voice would turn many a head. In fact, the Edward’s maid Henrietta (Lisa Horner) falls head over heels for him at first sight.

There’s one slight problem with the romantic prospects of Ben and Caroline. You see, he’s a . . . well, not to put too fine a point on it, Ben is a “Negro,” the issue of a marriage between his shipbuilder Italian father and an African beauty from Mauritania. (The frequent use of the word “Negro” in the script occasioned an apologetic and exculpatory note in a programme insert. O tempora! O mores!)

Whether out of jealousy or because he sees the war as a way out of his dead-end job, Frederick, a newly-minted corporal in the Massachusetts militia, arrives to arrest Ben for “consorting with the enemy.” It doesn’t go well.

Norm Foster is known for his light-hearted comedies and not for trenchant social commentary. While it is not on a par with his best work, 1812 does have its quota of well-earned laughs. It also manages to deal deftly with weightier issues such as the futility of war, the madness of governments, the waste of young lives cut short, the proper role of women in society, and racial prejudices and the roadblocks they create for normal interpersonal relationships. All these are handled with Foster’s trademark light touch and they are all the more effective for that.

Jim Mezon, a 33-year veteran of the Shaw Festival, has directed his 1812 cast to act broadly, in an almost sketch comedy style. That may be appropriate to the material, but it mutes the deeper resonances that a more naturalistic approach might have afforded. Nonetheless, Denny, Clark, and Dwyer bring some nicely observed moments of truth to their characters.

As usual, designer Peter Hartwell has created a simple but effective set. The 72-seat outdoor venue, nestled in the courtyard of a small building on the fort’s grounds is delightful, at least when the weather cooperates. Given the intimate scale, I was a bit surprised that the actors were mic’ed, some of them distractingly so.

If you go, be aware that it is a fair bit of a hike from the parking lot ($6) to the ad-hoc theatre and I saw no accommodation for those with mobility issues. Admission comes with a pass to the Ft. George historical site good until October 31, 2022.

The play runs until June 23, 2022. For more information, visit the Foster Festival website.

Don’t miss another review. Follow OntarioStage on Twitter.