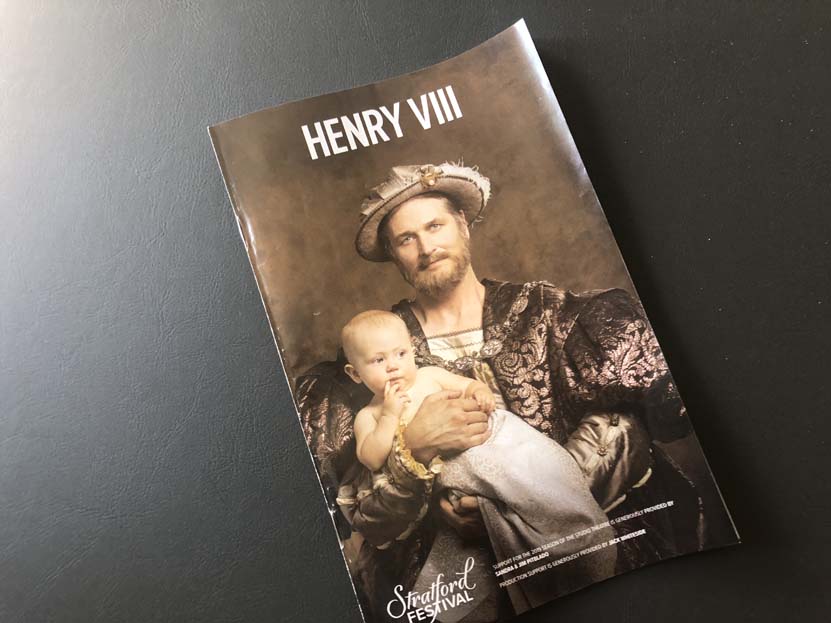

Henry VIII at The Stratford Festival

Henry VIII is one of William Shakespeare’s last plays and one of the oddest. It would seem that the play was designed to compete with the growing popularity among the Globe’s monied clientele of court masques, elaborately staged pageants that featured rich costumes and ingenious special effects. Ironically, the attempt to mimic the court proved catastrophic. One special effect featured a cannon fired from atop the Globe. An ember fell on the thatched roof and the theatre burned to the ground.

Ideally, a new production would reflect that history (minus destroying the theatre, of course), with a large cast, magnificent costumes, elaborate effects, and a splendiferous set in the 1,200-seat Festival Theatre. Alas, director Martha Henry has to make do with the intimate confines of the Stratford Festival’s 250-seat Studio Theatre and a cast of just twenty-two, with considerable doubling. Despite these constraints, she does a remarkable job of creating a certain amount of spectacle. One can sympathize with the decision; Henry VIII is a little known Shakespeare that would not have the box office draw of a Shrew or a Romeo and Juliet. Even so, one can wish.

One thing that sets this play apart from others in the canon is that the title character is not really at the center of the action. True, he is a powerful and often frightening presence throughout the play, but he is often offstage. Shakespeare turns his attention largely to the effect dynastic politics, not to mention Henry’s whims and ambitions, have on those around him.

Shakespeare brings to the foreground three characters whose privileged places in society were brought to ruin during Henry’s reign. The Duke of Buckingham was executed; Cardinal Wolsey was stripped of his offices and properties, and died in disgrace; Henry’s once and perhaps still beloved wife, Catherine of Aragon, was divorced so that Henry could marry Anne Bullen (or Boleyn) and sent into humiliating, if comfortable, house arrest. Each of them has a beautiful soliloquy in which they appeal to the audience’s sympathies (Catherine is also accorded a heart-rending death scene) and each of them is amazingly affecting, even Wolsey who has been depicted as the lowest form of Machiavel.

The original title of the play was All Is True. (It was subsequently demoted to a subtitle.) One can only assume that the contemporary audience had firm, and perhaps uniformly negative, opinions of all of these characters. Was Shakespeare offering “alternative facts” and suggesting with his title that historical truth is ultimately unknowable?

Shakespeare does not neglect to give Henry his own arc in the play, although it takes a good actor and director to make it manifest. We see him first as a cheerful sovereign obviously deeply in love with his wife but shaky on the details of governance (Taxes? What taxes?). By play’s end he has become more Machiavellian than Wolsey himself. The penultimate scene in the play in which he makes the newly appointed Archbishop Cranmer his golden boy and forces the entire council of state, who had to a man opposed Cranmer’s ascension, tow the new party line is chilling indeed.

Ultimately, any psychological verisimilitude falls away with the birth of Elizabeth and an outburst of patriotic pride that beggars the imagination. Could Henry, for whom producing a male heir was all-important, really have been that thrilled with the arrival of the future Queen Bess? One thinks not.

As mentioned earlier, director Henry does a good job of dealing with her limited resources and creates a suggestion of the pomp the piece demands, aided in no small measure by designer Francesca Callow’s increasingly colorful if often anachronistic costumes. I doubt Anne Bullen (Alexandra Lainfiesta) ever danced in a dress with two waist-to-floor slits, but who’s complaining?

For the most part, Ms. Henry keeps a firm hand on the rudder as she marshals an exemplary cast, making sure that the many historical figures, only a few of whom a modern audience is likely to remember, remain distinct. An unfortunate misstep occurs in a scene in which Cardinal Wolsey throws a party. Instead of showing the Cardinal’s real sin — his betrayal of his office in favor of ill-gotten wealth and wretched excess – she depicts the Cardinal as a kinky voluptuary complete with red silk pajamas and purple boa.

As King Henry, Jonathan Goad does a good job of showing us a king driven to ever more equivocal ethical decisions by the pressures of a rigidly patriarchal power structure. But the true star performance of the piece comes from Irene Poole as Catherine. Her confrontation with Wolsey is as startlingly powerful as her death scene is poignant; along the way she depicts beautifully the ironies and injustices of her position as the daughter of a king reduced to mere pawn.

The estimable Rod Beattie seems miscast as Wolsey. Initially he conveys little of the stature or evil the part demands. His line readings are often flat and he reminded me in turn of one of his Wingfield personas, then of an elderly Mr. Bean, and then of Wallace Shawn. Even so, in his scene after the king discovers his perfidy, he was quietly devastating.

Other solid work comes from Tim Campbell as Buckingham, although at the performance I saw he skipped the curtain call, which struck me as a breach of protocol. Festival stalwarts Wayne Best, Brad Hodder, Stephen Russell, Scott Wentworth, and Rylan Wilkie all lend excellent support.

All in all, this was as good a rendition of this intriguing play as one could expect given the obvious restraints. I only wish Ms. Henry had been given the Festival Theatre stage and the budget required to give us a real appreciation of what Shakespeare had in mind.

Some final observations: There seems to be some consensus that this play was a collaboration between Shakespeare and John Fletcher, although some preeminent scholars disagree. The program gives the Bard sole credit and I am not inclined to argue with that. The bit of pseudo-Elizabethan doggerel, written by a cast member, that closed the show didn’t help.

More Reviews

To access the complete archive of reviews listed alphabetically CLICK HERE.