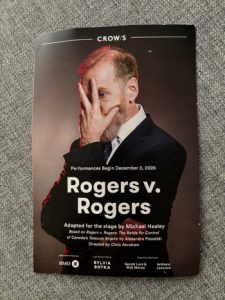

Rogers v Rogers At Crow’s Theatre

After seeing Michael Healey’s brilliant (and brilliantly funny) The Master Plan at Crow’s Theatre not even the dreaded Canadian winter could keep me from coming to Toronto to see his Rogers v Rogers. The fact that Tom Rooney was playing all fifteen characters was icing on the cake.

Rogers v Rogers is based on the book “Rogers v Rogers: The Battle for Control of Canada’s Telecom Empire” by Globe and Mail correspondent Alexandra Posadzki. Posadzki’s book is a meticulously researched account of corporate shenanigans mixed with an irresistible tale of siblings fighting over the fate of a mega-corporation founded by their legendary father. Shades of Succession! Indeed a Cameo video featuring Brian Cox, who starred in that show, makes <ahem> a cameo appearance in Healey’s adaptation.

Although the company’s roots go back to 1914, Ted Rogers founded Rogers Communications in its present iteration in 1960. The senior Rogers didn’t feel his son Edward, portrayed here as an insecure man with a stammer, was up to becoming CEO after his death, so he appointed him Chairman of the Board, which gave him considerable sway over corporate affairs. It proved not to be the wisest of decisions

I had expected Healey to take a dense and complex tale of corporate hijinks and spin it into comic gold, while remaining absolutely true to the facts of the case. While there is plenty to laugh at in Rogers v Rogers, Healey has more serious fish to fry.

Rogers v Rogers shines a sharp satiric spotlight on what Healey obviously sees as a fatal flaw in the Canadian character, one that allows corporations to stifle competition by growing ever larger and more powerful through mergers and acquisitions.

Another tactic at which he takes aim is corporations like grocery giant Loblaws buying up multiple brands and maintaining their separate identities while controlling them all from on high, thus giving the consumer the mirage of competition as prices ratchet ever higher and produce the $4 tomato.

Perhaps because of this not so hidden agenda, and with a gimlet eye cast on the lawyers who lurk in the shadows, Healey goes to great lengths at the opening of the show to stress that what we are about to see is not journalism, not a documentary, but fiction. The programme repeats the disclaimer.

The tale of Rogers v Rogers is told to us by Matthew Boswell (Tom Rooney) head of Competition Bureau Canada, a government entity of which only one person in the audience had ever heard. (He asked.)

The Bureau is “an independent law enforcement agency that protects and promotes competition for the benefit of Canadian consumers and businesses.” However, if Healey is to be believed, it has failed royally in fulfilling its mission. It has never succeeded in quashing a competition-killing merger, although not for lack of trying.

At first I thought the name Boswell was subtle literary reference. It turns out Mr. Boswell is a real person, but presumably highly fictionalized. Since he is portrayed as something of a hero for the Canadian consumer Healey is unlikely to face a lawsuit.

As Boswell spins his tale he plays all the characters, 15 in all. It’s an awkward device that didn’t always work for me. The extent to which it does is attributable to the substantial talents of Rooney, arguably Canada’s greatest living actor.

The 90-minute, intermission-less Rogers v Rogers place in a handsome high-tech boardroom concocted by Joshua Quinlan (sets), Imogen Wilson (lights) Nathan Bruce (video), and Thomas Ryder Payne (sound), all of them doing exceptional work. The set is bathed in red, Rogers’ corporate colour, making it look perhaps intentionally like the boardroom from hell.

Behind the set-wide boardroom table is a video wall that is constantly active. In many respects it’s the co-star of the show. Even the floor is one large video screen. In the final confrontation among the board and the siblings the video wall, indeed the entire set, is turned into a massive Zoom call. Small cameras mounted on the downstage edge of the boardroom table allow Rooney to play his sisters and his mother on the video wall. Clever as the dickens, but not entirely successful.

All of this is highly reminiscent of the style director Chris Abraham used in The Master Plan, although Rogers v Rogers uses a traditional proscenium approach rather than the in-the-round setting of the earlier Healey play.

When Abraham used the same style in Octet, I was afraid it would become a Crow’s Theatre cliche, but here it works perfectly. It makes Rogers v Rogers a great deal of fun to watch and gives Rooney a terrific showcase for his bravura performance.

In the end, Competition Bureau Canada fails to stop the merger of Rogers and Shaw, another telecom behemoth. Thus, the highly fictionalized Boswell ends the show with a not too subtle plug for Freedom Mobile, a plucky, still independent telecom that offers a modicum of competition in the cell phone service sector.

Footnote: A programme note observes “something we have come to understand at Crow’s: audiences are hungry for stories about our city – stories that let us see our selves, and our politics, reflected.” Well, DUH! I might humbly suggest that Crow’s could learn from the example of the Blyth Festival which has been doing precisely that for over 50 years.

Rogers v Rogers continues at Crow’s Guloien Theatre through January 17, 2026. For more information and to purchase tickets visit the Crow’s theatre website.

For a complete index of reviews CLICK HERE.

Don’t miss another review or blog post! SUBSCRIBE HERE