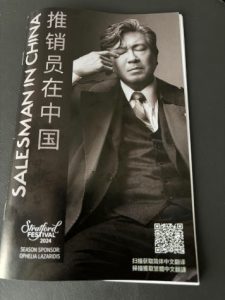

Salesman In China At The Stratford Festival

The Stratford Festival has a major hit on its hands with the transcendent, Broadway-worthy world premiere of Salesman in China, by Leanna Brodie and Jovanni Sy, directed by Sy. Now playing to full houses at the Avon Theatre, it is an imagined recreation of the events surrounding the production of Death of a Salesman in Beijing in 1983, directed by Arthur Miller himself and starring famed Chinese actor Ying Ruocheng.

The play is based on autobiographies of Miller and Ying, both of which have been added to my reading list. The playwrights are careful to note in the programme that, while the events presented are accurate, many interactions in Salesman in China have been imagined.

The play unfolds in both English and Mandarin and the stage has been raised several feet to accommodate a black strip on which subtitles in both languages are projected. It works surprisingly well, although the lady seated next to me had trouble reading them until she snagged a booster cushion at intermission. The vertically challenged should take note and request a booster on entering the theatre.

Salesman in China is set in 1983 when China, having suffered the two disasters of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution under Mao, was coming to its senses under Deng Xiaoping and, as we can see in retrospect, taking the first tentative steps that would bring it to the brink of world domination today.

Part of that journey involved opening up to the rest of the world, allowing Ying (the astonishing Singaporean actor Adrian Pang) to realize one of his dreams, playing Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman under the direction of Arthur Miller (a towering Tom McCamus). As Ying says, if China is to be a great nation it must build bridges to other great nations.

As it turns out, it’s not that simple. A major theme is stated early when Miller brushes aside concerns about some of the cultural specifics of Death of a Salesman. At base, he explains, it’s a play about fathers and sons. Indeed, so is Salesman in China. But again, it’s not so simple.

Miller and Ying are depicted as committed artists with deep respect for each other but each has ghosts haunting him. For Ying it’s memories of having failed his father, a university professor who fled to Taiwan after the revolution and who appears mockingly to Ying throughout the play. As if that wasn’t bad enough he can’t shake the memory of Auntie Zhao (Harriet Chung), beaten by Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution.

For his part, Miller is wrestling with his status as an iconic American playwright yet also something of a has been, remembered by most people as the lucky son of a gun who was married to Marilyn Monroe. He also confides to Ying the fact that his first son, born with Down syndrome, was packed off to an institution never to be acknowledged again. The Beijing production of Salesman offered a chance to reclaim something of his mojo.

Ying has worshipped Miller and his play for years. For his part, Miller sees Americans and Chinese as sharing a common humanity. Brodie and Sy do a profound job in Salesman in China of revealing the disconnect between Miller’s rosy view of a common humanity and the reality of a China dealing with its own moral evolution in its own distinctively Chinese way.

Miller, his memories of HUAC still raw, has a hard time understanding Ying treating the Cultural Revolution as, in Miller’s words, like a summer camp. Ying’s wife, You Shiliang (Jo Chim) acidly points out that those who live in a glass house built on slavery shouldn’t throw stones.

It’s all laid out, warts and all, including the pervasive racism of China’s Han-supremacism. A very funny, but on reflection deadly serious episode, considers the outrage of the Chinese National Theatre’s makeup and wig department when Miller bridles at their insistence on creating racist depictions of Westerners. Brodie and Sy drive the point home about the cultural disconnect in a touching speech, delivered in a language Miller can’t understand, in which a wig maker (Derek Kwan) explains the devotion he lavished on creating a blonde wig as a sort offering to the great Arthur Miller.

Ying defends these theatre artists by pointing out that Miller wanted the company to bring their Chinese sensibility to his play and this is the way Chinese imagine Westerners in a theatrical context.

This is just one of the ways in which Salesman in China is very much of the present moment, as the United States, Canada, and the West face off against an increasingly assertive China over cultural, economic, and strategic hegemony.

Salesman in China is also, not so incidentally, a love letter to the theatre and the actor’s art. Anyone who has logged any time in “showbiz,” even on an amateur level, will find much to smile at. I loved the way stage manager Ding (Howard Dai) moved from bored party-line martinet to enthusiastic showbiz trouper.

I was also impressed by how Brodie and Sy depicted the artistic journey of the Chinese cast. They were confronted with a script that was totally alien. For starters, traveling salesmen and life insurance didn’t exist in China, and in this post-Mao era their ignorance of the West was profound. They asked all the right questions: who are we, where are we, why are we saying these things?

Slowly, with dignity and unimpeachable artistic integrity they find their way to realizing Miller’s vision in a Chinese context and in a way that is true to their artistic instincts.

Phoebe Hu is quietly brilliant as she creates Linda Loman, gently but insistently pushing back against Miller’s direction until she elicits explanations that enable her to create a character on her own terms. Agnes Tong is alternately funny and touching as a very proper Chinese girl wrestling with how to play a very Western slut; in the end she rocks a slip borrowed from Miller’s wife Inge (a solid Sarah Orenstein) and even allows herself to receive a pat on the bum and appear to enjoy it.

The production is as impressive as the script. Sy’s staging is positively lyrical. From the opening tableau that invokes the famous image on the cover of the printed script of Death of a Salesman to the heart-rending denouement, Sy holds the audience in the palm of his hand.

He has made the most of a gifted cohort of artistic collaborators. Atmospheric, almost cinematic lighting by Sophie Tang, spare and malleable sets by Joanna Yu, and projections by Caroline MacCaull and Sammy Chien, move the action effortlessly from scene to scene and backwards in time.

Add in a wonderful score by Alessandro Juliani, a recreation of a Mao era propaganda opera by Harriet Chung, and evocative costumes by Ming Wong and you have a Salesman in China that is part fever dream, part fly on the wall documentary, and altogether enthralling.

Salesman in China continues at the Stratford Festival’s Avon Theatre through October 26, 2024. For more information and to purchase tickets visit the Stratford Festival website.

For a complete index of reviews CLICK HERE.

Don’t miss another review or blog post! SUBSCRIBE HERE.