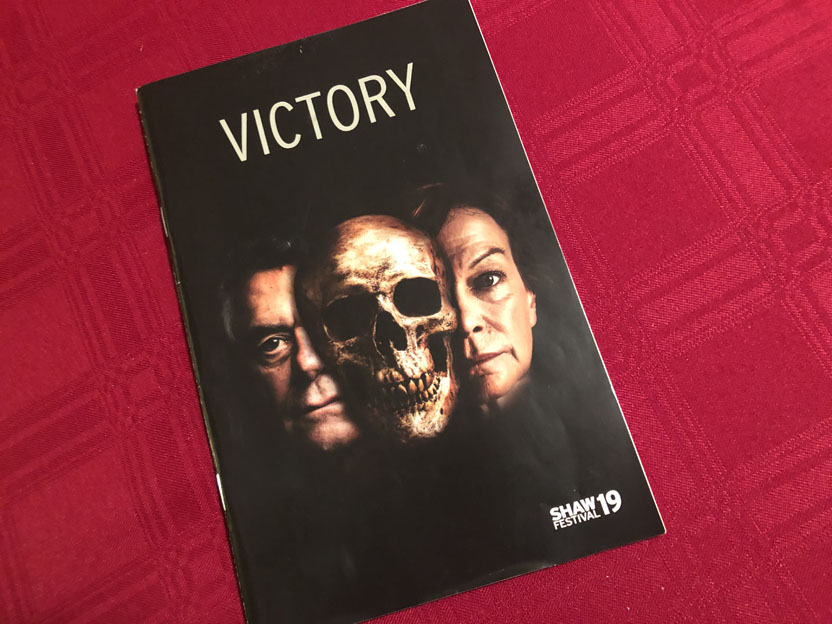

Victory at The Shaw Festival

Howard Barker is the bad boy of British theatre. He revels in filth, flatulence, four-letter words, and fornication displayed on stage with all the verisimilitude that the law allows in plays set for the most part in past eras and other countries — for the “distancing effect” he says.

“A good play puts the audience through a certain ordeal,” he once told The Guardian. “I’m not interested in entertainment.”

Victory, his 1983 historical drama being offered up by the Shaw Festival in the intimate confines of the Studio Theatre, makes good on that promise — or is it a threat?

Set during the restoration of the English monarchy in the 1660s, the play follows the trials of Mary Bradshaw (Martha Burns), widow of John Bradshaw, one of those who had signed the death warrant for Charles I. Bradshaw was dead when Charles II returned in triumph to England, but he was nonetheless charged with treason, exhumed, hung, drawn, and quartered. His widow attempts to gather the decaying pieces of his body, which have been put on public display around London, so she can bury them. It doesn’t go well.

Along the way, she meets King Charles II (Tom McCamus), his mistresses Nell Gwynn (Deborah Hay) and Devonshire (Sara Topham), and Ball, a randy cavalier (Tom Rooney) whose mission of avenging the overthrow and execution of Charles I seemed to involve raping every Cromwellian woman he could lay his hands on.

There’s not much of a plot. Plot was not one of Howard Barker’s major concerns. Given the politics of the era, one might expect some sort of political message. But “I have contempt for messages in the theatre,” Barker once proclaimed. Bradshaw’s widow is the only character who evolves significantly during the course of the play and given the human quirk of pareidolia, which causes us to see images in clouds and other random patterns, I decided the “message” was that the secret to survival in times of upheaval is to accommodate yourself as best you can to the new dispensation. At play’s end Bradshaw’s widow is married to the cavalier who raped her, caring for his child, and still carrying a burlap sack filled with the bits of her dead husband.

Otherwise the play seems rather random, a succession of short scenes that seek to epater les bourgeois. At one point, I was reminded of the New Yorker humor piece about new warning signs in the theatre — “Warning: This play contains nudity. However it doesn’t involve the actor you would prefer to see naked.” Barker succeeds fairly well in shocking us, so well in fact that a fair number of the bourgeois in the audience epater-ed themselves right out of the theatre at intermission.

I’m not sure whether this was Howard Barker’s idea or an inspiration of the director, but for the final scene of the first act the entire audience was forced to leave the theatre and either descend a long flight of stairs or cram into a tiny elevator to reach a windowless room with too few chairs to accommodate everyone. It was a pointless exercise, which given the advanced age of many of the audience members was also rather cruel.

For all its insistence on repelling its audience, Victory is now “an acknowledged masterpiece” and I have that on no less authority than the playwright himself, who tells us that in a program note. Well, maybe.

If I’ve been a little hard on Mr. Barker it’s only because his pompous self-regard makes it irresistible to snipe. To give him his due, the play is never boring even if it is never truly involving. A fair amount of credit must be given to director Tim Carroll, who has wisely decided to stage the play on a completely bare stage, which brings a refreshing feeling of space to the Studio’s small theatre-in-the-round playing area. Rachel Forbes’ terrific costumes along with the occasional chair or table and Kevin Lamotte’s sensitive lighting are all the scenery needed.

Carroll has also elicited excellent performances from his principal actors. Tom McCamus seems to be specializing in deranged English monarchs and he does it very well. Sara Topham manages to maintain her dignity even when she is waving a semen-besmirched hand in search of a napkin. When Deborah Hay doubles as a doddering old courtier she makes one forget the inanity of much of the random gender swapping that goes on these days. Finally, Martha Burns brings a deep sense of humanity and realism to widow Bradshaw, no matter how improbable the path the text requires her to tread.

In a program note, Tim Carroll says, “Discovering Howard Barker blew my mind wide open.” Fair enough, but why is Shaw doing this play? I think theatre people are drawn to this sort of “transgressive” material in much the same way that comedians gather from time to time to drink copious amounts of alcohol and compete to see who can tell the filthiest jokes. There’s something liberating in breaking down barriers of propriety and taste. Maybe the exercise gives actors access to darker realms of the imagination and helps them go on to create more compelling characters in other plays. There’s definitely a place for this kind of exploration. But at Shaw?

Perhaps there’s an unlit basement room with not enough chairs to accommodate the audience somewhere in Toronto.

Howard Barker’s Victory continues in repertory at the Shaw Festival’s Jackie Maxwell Studio Theatre through October 12, 2019.

The Shaw Festival

www.shawfest.com

(800) 511-7429

(905) 468-2172

More Reviews

To access the complete archive of reviews listed alphabetically CLICK HERE.