Handcuffs At The Blyth Festival

The Blyth Festival’s epic presentation of James Reaney’s so-called Donnelly Trilogy, concludes with Part 3: Handcuffs. As abridged, adapted, and directed by Gil Garratt, it goes out in something of a blaze of glory.

(To avoid needless repetition, I refer readers to my reviews of Part 1: Sticks and Stones and Part 2: St. Nicholas Hotel.)

Handcuffs covers the few years leading up to the the Donnelly family massacre in February 1880.

The animosity towards the Donnelly family, now in full flower, was part of a feud that traced its origins to County Tipperary, whence many of the Irish who settled along the Roman Line in Biddulph hailed. There the Donnellys and a few other families refused to join the “White Boys,” a group opposing both the British government and the Protestant faith. Romantic notions of Irish nationalism aside, it was what we would today call a terrorist organization.

In Canada, those sentiments lived on, now coloured by Canadian politics and commercial rivalries, the roots of which were limned in St. Nicholas Hotel.

Handcuffs reveals the baleful influence of Ontario’s Roman Catholic hierarchy in the affairs of Biddulph and Lucan. The Church traditionally backed the Conservative Party and the bishop (James Dallas Smith) is eager to see a Roman Catholic Conservative win the Biddulph riding.

The plan comes a cropper when the Donnellys and other Catholics stay true to the Liberal party – there was no secret ballot in those days – and the bishop’s anointed candidate loses.

He appoints Father Connolly (Paul Dunn) to the Donnelly’s parish in the hopes of bringing them to heel. Influenced by the slanders spread against the Donnellys by members of a secret society descended from the Tipperary White Boys, Connolly forms the “Biddulph Peace Society.”

The newly appointed constable, James Carroll (Geoffrey Armour), the de facto head of the secret society, exults that now that he controls the law and has the Church behind him the way is clear to settle the score against the Donnellys once and for all.

Handcuffs boasts the usual strong performances from all concerned. Randy Hughson and Rachel Jones are once again exemplary as the elder Donnellys and Masae Day is poignant as the Donnelly niece who arrives in Canada mere months before she is slaughtered.

Geoffrey Armour is suitably despicable as the villainous Carroll and Paul Dunn is especially fine as Connolly, his meatiest role of the trilogy. It it uncertain to what extent the historical Connolly was aware of the implications of his actions and in the aftermath of the massacre he suffered pangs of regret, but in Reaney’s and Garratt’s telling he is a willing instigator and participant in the crusade against the Donnellys.

As fine as the performances are, the greatest contributions to Handcuffs come from the creative team of Beth Kates (sets and lighting), Lyon Smith (sound design), and director Garratt.

The staging of the massacre of the Donnelly family and the burning of the home that became their funeral pyre is a coup de théâtre that belies the modesty of the Harvest Stage. The final stage picture, under a dark Huron County sky, wreathed in the smoke from the smoldering ruins of the Donnelly homestead, is haunting.

Now that Handcuffs has opened, Blyth is presenting the entire trilogy on successive nights, one part per night.

Handcuffs continues in repertory through September 3, 2023. For more information and to purchase tickets, visit the Blyth Festival website.

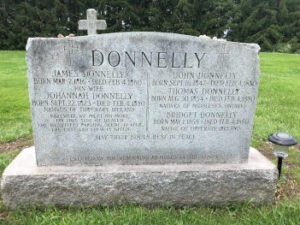

(image: The Donnelly family grave at St. Patrick’s church on the Roman Line.)