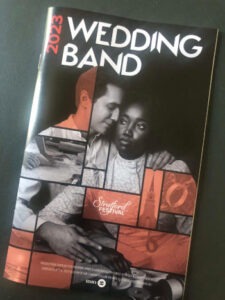

Wedding Band At The Stratford Festival

The Stratford Festival has another triumph on its hands in the form of Sam White’s searing production of the 1962 Alice Childress masterpiece, Wedding Band. Except for a mention in the author bio, the programme omits the play’s telling subtitle, A Love/Hate Story in Black and White, but it is apt.

Set in a mulatto ghetto in Jim Crow South Carolina in 1918, Wedding Band tells the story of the illicit love between Black seamstress Julia Augustine (Antonette Rudder) and white baker Herman (Cyrus Lane). The two dream of escaping to New York where they could be married legally, but poverty, fear of the unknown, and ultimately the flu pandemic of 1918 prevent them from leaving.

Childress takes on some major themes in Wedding Band. The blatant racism of the South is the first thing that will strike a contemporary audience. Then there is the injustice not just of anti-miscegenation laws but a whole panoply of legal strictures that reduced women to second- and third-class status. Nor does Childress ignore the internalized prejudices of the Black underclass, often directed at one another.

That’s a lot to be getting on with and if you read the programme notes before the curtain rises, you might think you will be in for some rather heavy-handed preaching. Nothing could be further from the case in Childress’s beautifully realized portrait of the world in which Julia’s and Herman’s sad story unfolds.

In Wedding Band, Childress gives us a portrait of a bygone world (well, let’s hope it’s bygone) as detailed and evocative as a Heironymus Bosch painting. There are no stick figures, no straw men, no cardboard villains here. Every character has sprung full-born from the fertile imagination of the author. Each of them, even the most minor, has a compelling backstory, sketched by Childress in deft strokes, giving talented actors (more on them anon) a chance to shine.

Julia has moved into a house owned by Fanny Johnson (Liza Huget), a self-made woman proud of the small gains she has made in the white man’s world. Next door live Lula Green (Joella Crichton) and her adopted son Nelson (Micah Woods), a strapping young man on leave from the U.S. Army that has just returned from fighting the war to end all wars, bring contagion home with it.

Also part of this world is Mattie (Ijeoma Emesowum) the illiterate caretaker of a young white girl who plays with Mattie’s daughter of about the same age. Everything we need to know about the dire poverty of this little corner of the South is made palpable by Mattie’s terror when a quarter goes missing.

A frequent visitor to the neighborhood is a white tradesman, identified only as Bell Man (Kevin Kruchkywich), who peddles necessities and such like to the poor Blacks of the area. Friendly on the surface, he is not above soliciting sexual favors in exchange for a pair of hose.

Herman falls victim to the flu pandemic and as his condition worsens, Julia is faced with a conundrum given the illegal nature of their situation. She summons Herman’s mother (Lucy Peacock) and sister (Maev Beaty) to take him home where he can be treated.

This provokes a confrontation that boils over into a volcanic exchange of screaming racist vitriol and insults (in both directions) that is as breathtaking as it is cathartic. No punches are pulled and no slurs excised. For once, the usually laughable programme warnings about “triggering language” made a sort of sense.

The love affair at the heart of Wedding Band is limned in the most prosaic of terms. Childress uses their quotidian concerns rather than gushing protestations of love to show us how deeply Julia and Herman care for each other. These aren’t heroes or culture warriors; they are simply two ordinary people who had the luck and misfortune to find someone they loved.

The white characters other than Herman are not, to put it delicately, very nice people, and even Herman has his racial blind spots. But then all the characters, Black and white, have their faults. Childress is skilled enough to show us what has shaped her characters and compassionate enough to depict each of them as to some extent victims of their time and circumstances.

Rather than soften the social critique that reverberates throughout Wedding Band, the suppleness of Childress’s technique enhances it.

This is playwrighting of the highest order, the kind that seems to elude most contemporary playwrights who create mouthpieces rather than fully rounded human beings living recognizable lives in recognizable surroundings and circumstances. This seems to be especially true of plays dealing with “controversial” social issues.

Wedding Band is the sort of play that, had it been given the kind of first-class Broadway production that made Williams and Miller household names, would have placed Childress on a similar plane. Why didn’t that happen? If you said “racism,” I’d have to say you’re probably on to something.

When Wedding Band finally received a New York production in 1972, it was dismissed as “pat” and “old-fashioned” by the leading critics of the day.

At long last, thanks to White’s masterful production and her superb cast, there can be no doubting Childress’s greatness now. I wish this production could move, cast intact, to Broadway so the New York theatrical establishment could repent its shortsightedness. Of course, transfers like that from Stratford seldom if ever happen. More’s the pity.

Antonette Rudder, who has been all but anonymous in two previous seasons at the Festival, emerges in Wedding Band as a leading lady of the first order. Her Julia possesses a quiet dignity and she only gains in stature as the play progresses. Cyrus Lane, a Festival veteran, is giving the finest performance I have ever seen him give as the sympathetic but rather hapless Herman.

In fact, everyone in the cast is superb. Liza Huget, Ijeoma Emesowum, and Joella Crichton all turn in beautifully modulated performances. I was especially taken by Micah Woods’ depiction of a proud man ground down by the injustices of the era. Not even his abundant patriotism earned him any credit – “Don’t let that uniform go to yo’ head, boy!”

Lucy Peacock, Maev Beaty, and Kevin Kruchkywich give the sort of no-holds-barred portrayals of craven racists that must have forced them to discover some very dark and unpleasant corners of their inner beings.

All of this is credit to White’s steady directorial hand. She has staged Wedding Band efficiently on the Tom Patterson’s elongated thrust with assistance from Richard H. Morris Jr, who did the sets and Kathy A. Perkins who handled the lighting chores. I couldn’t help feel, though, that she might have preferred a proscenium.

There were other nice touches as well. Sarah Uwadiae contributed well-observed period costumes. The rousing rendition of “Climbing Jacob’s Ladder” that opens the show and other brief musical moments are delightful. Beau Dixon gets credit as composer and Debashis Sinha for sound design.

I first came to love the Stratford Festival for the Shakespeare. Later I fell under the spell of the musicals. This season I think it is the dramas I will cherish the most. Wedding Band, along with Casey and Diana, are productions of which the Festival can be rightly proud.

Wedding Band continues at the Tom Patterson Theatre through October 1, 2023. For more information and to purchase tickets visit the Stratford Festival website.

For a complete Index of Reviews, CLICK HERE

Re: “The only softening of the text I noticed in the play was the omission of a racist chant the young girls employ while jumping rope.”

The racist chant is sung by the girls while jumping rope, exactly as written in the text.

Many thanks for the correction!

Amazing play indeed, one small correction in the review, the racist chant from the kids while jumping rope was not cut and is indeed in the show.

Many thanks for the correction!

An error in the review, called to my attention by two readers (thanks again) has been corrected. My bad.