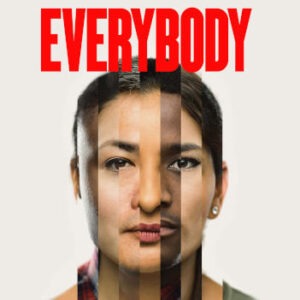

(Image: Shaw Festival)

Everybody At The Shaw Festival

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ Everybody is an exceedingly entertaining modern riff on the medieval morality play Everyman that works remarkably well in the intimate confines of the Jackie Maxwell Studio Theatre at the Shaw Festival.

Everyman, officially The Somonyng of Everyman, is the earliest surviving dramatic work in the English language, dating from the late 1400s. Frankly, it’s not a laugh riot, dealing as it does (major spoiler alert) with death. Not just any death but the death of every man, which in that prelapsarian era meant all mortals, male and female. Since it is long since out of copyright, the full text of the original is readily available online. You can read a version in lightly modernized English here. But if you’d like to be reassured that you made the right decision by not pursuing an advanced degree in English Literature you can read the original here. Kidding aside, it’s worth the read in either version.

Jacob-Jenkins’ modernization begins with the title – Everybody. No gender discrimination here! But it goes much further, infusing the play with a wicked and very modern sense of humor, while remaining remarkably faithful to the source material, which he both explicates and quotes from. Like its inspiration, Everybody is a morality play, which means among other things that it deals in allegory. As we are told, some of the people in the play are not actually people. In other words, some of the actors portray abstract concepts — Friendship, Kinship, Worldly Goods (or in Jacob-Jenkins’ rendering “Stuff”).

I am reluctant to reveal too much of the structure of Everybody since doing so would spoil some of the play’s best conceits. Suffice it to say that five people, of varying races and genders, who are pretty much like us (they are drawn from the audience, after all) are summoned to confront Death. One of them will actually —here’s that spoiler alert again — die before our very eyes.

In an inspired bit of meta-theatrical inspiration, Jacob-Jenkins selects his “victim” via a tombola — one of those revolving drums from which lottery numbers are drawn. A better metaphor for the role of fate in human life would be hard to come by. One lucky actor gets to play Everybody, while the other four are assigned allegorical roles by the number they draw. This means, of course, that all five actors must know five separate roles, making this something of a pentathlon of acting. Don’t be surprised if you are tempted to see it again to see the role reshuffled; I’ve already booked my tickets.

I will not name the actor who played Everybody or any of the other personages at the performance I saw since it is statistically unlikely that you will see the same line up at the performance you attend. (Apparently, there are 120 different possible combinations.) But if the performance I saw is anything to go by (and I strongly suspect it is), this is a superb group of actors. So let me simply list them in alphabetical order, all identified in the program as “Somebody”: Julie Lumsden (the wife in Gaslight), Michael Man, Kiera Sangster, Travis Seetoo (the Microbe in Too True To Be Good), and Donna Soares (the Patient in Too True).

Needless to say, Everybody is rather distressed to learn they are going to die. Death cuts him some slack by ducking out to change for the big moment, telling him that he’s welcome to find someone to follow him into the hereafter. Enter those allegorical personages. All of them are initially enthusiastic to see Everybody. And all of them back out when they realize what’s being asked of them. The moral (hey, it’s a morality play) is that we all confront death alone and none of the things we cherish in life matter a great deal in the final analysis.

As the end approaches, Everybody’s most personal attributes, Mind, Strength, Beauty, his Five Senses, also fall by the wayside. Everybody only takes one thing into that great beyond. Can you guess what it is?

Everyman is pretty bleak or perhaps it’s more accurate to say pretty orthodox in its religious outlook. “Ite, maledicti, in ignem eternum,” God bellows at the end. “Go, cursed one, into fire eternal!” In Everybody, Jacob-Jenkins serves up a kinder, gentler vision of the afterlife. Indeed, it’s not much of a vision at all since even Death seems to be uncertain what happens once we have shuffled off this mortal coil.

I found the production to be first rate, thanks to a stellar cast that includes, in addition to the five Somebodies, a delightfully ditzy Deborah Hay in multiple roles, the droll Sharry Flettt as Death, and a hilarious Patrick Galligan in a tiny role at the play’s end. This version of the play is sprinkled with several allusions to the Shaw Festival itself — Galligan excuses his late arrival by asking in amazement “Do you know how many theatres there are here?” — which led me to wonder if, like Goldoni before him, Jacob-Jenkins encourages tweaks to appeal to local audiences.

Director László Bérczes, who delivered a splendid Glass Menagerie for Shaw in 2019, has done a wonderful job of bringing the play to life. He is establishing himself as one of Shaw’s premier directors. He has once again called on fellow Hungarian Balázs Cziegler to design a bucolic set for the narrow stage of the Studio. Dominated by a beautiful gnarled tree, it struck me as a softer evocation of the bleak road on which Vladimir and Estragon await an uncertain fate. Nice work, too, from Sim Suzer (costumes), Kevin Lamotte (lights), and Claudio Vena (original music and sound design).

Despite its seemingly downbeat theme, Everybody is oddly, refreshingly uplifting. Like malt, it does more than Milton can to justify the ways of God to Man.

Don’t miss another review. Follow OntarioStage on Twitter.

Great review of an eternal topic.