The Drawer Boy At The Blyth Festival

The Drawer Boy by Michael Healey is considered by some the greatest Canadian play ever written. That is certainly a defensible position if we are to judge by the revival the play is receiving at the Blyth Festival in a production for which the adjective incandescent is not as hyperbolic as it might sound.

Set in 1972, The Drawer Boy tells the tale of Morgan and Angus, aging bachelors, life-long friends, and co-owners of a farm not far from the Blyth Festival. Their hardscrabble but predictable life is disrupted by the arrival of Miles, a gullible young actor in a theatrical collective from far off Toronto which is creating a collaborative piece about farming. Miles offers free labour in exchange for the opportunity to observe farm life first hand and take notes from which he will craft his own contributions to the collective effort.

Morgan and Angus are World War II vets whose life has been visited by tragedy. Before the war, Angus was on a very different trajectory. A gifted draftsman – hence the nickname “the drawer boy” – he was destined for college when Morgan, a resolute son of the soil, convinced him to set off on the “adventure” of war. Angus was severely wounded in an air raid in England, an event that has left him with a steel plate in his head and no memory. He lives in an eternal present. Each day Miles must reintroduce himself. “My name is Miles and I’m staying with you and Morgan to learn about farming so I can write a play about it.”

Much of the play is given over to humor as Morgan twits the clueless Miles about life on the farm, introducing him to the arcane arts of crop rotation and egg shuffling, and the mysteries of the “short handled insilage fork” (a dessert fork actually) with which Miles is expected to salvage the undigested corn from cow droppings so this “fortified” food can be fed to the chickens.

But there are darker currents beneath the laughter. As Angus is exposed to the equally mysterious world of theatre – he and Morgan are invited to a rehearsal of the play in progress – glimmers of recognition enter his darkened memory. He begins to recognize Miles on sight. When Miles recounts his performance as Hamlet, an interpretation roundly condemned by the critics as “too Canadian,” Angus begins to grasp the relationship between made up stories and reality. It’s a slippery slope and, while the play begins in laughter it ends in tears.

The Drawer Boy is based on the experiences of Miles Potter, who participated in the creation of The Farm Show in 1972 by the “experimental” theatre company Passe Muraille (“Beyond the Walls”). It was a seminal production that in many ways serves as a kind of origin story for the Blyth Festival itself, which was founded a few years later. Its mission was to present new plays that reflect the rural life of the surrounding communities. Many of Blyth’s productions are created collaboratively by actors in the company based on in-depth research into events and lore around southwestern Ontario.

The real Miles Potter was probably not as clueless as the Miles in The Drawer Boy. He went on to a distinguished and ongoing career as a director, including directing his wife Seanna McKenna as Richard III at the Stratford Festival in 2011. Playwright Healey also has a connection with Stratford. He provided the company with a shrewd and savvy updating of The Front Page a few seasons back.

Ironically, The Drawer Boy was originally intended for the Blyth Festival, but when the script was finalized the then artistic director rather inexplicably took a pass. So the play was first produced, fittingly enough, by Passe Muraille and went on to international renown. It has been translated into multiple languages including Hindi and Japanese. Now it has returned home.

The Drawer Boy has been given a sensitive production by Blyth Artistic Director Gil Garratt, who is blessed with something of a dream cast. Jonathan Goad, a Stratford Festival star making his Blyth debut, is rock solid as Morgan, the keeper of secrets, who has devoted his life to caring for his disabled buddy. Cameron Laurie is endearingly gormless as Miles. His interpretation of a “terrified” cow, desperate to give milk to avoid execution, is one of the play’s highlights. And Randy Hughson, who was a wonderful Scrooge for Blyth in 2019, cements his place in my estimation as one of Canada’s premier character actors as Angus. He can move from hilarious to heartbreaking in the course of a sentence. It’s a superb performance.

One of Garratt’s more inspired touches is positioning two musicians – fiddler and “multi-instrumentalist” Anne Lederman and percussionist Graham Hargrove – above the set, much in the way musicians were placed in Shakespeare’s time. Plus ça change and all that. They provide pre-show entertainment and incidental music and sound effects throughout the show. And the music Lederman serves up is the real deal, a far cry from the commercialized Nashville pablum that infests local “country” radio stations. Cloggers would have been a welcome pre-show addition.

As Garratt notes in the programme, this is a play about storytelling. It is also a play about the power of theatre and the mysterious ways in which entering into worlds of make believe helps us more fully inhabit our own reality. It also pokes gentle fun at actors, poor, helpless, gullible creatures that they are. And I mean that in the nicest possible way.

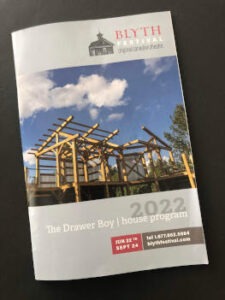

The Drawer Boy is being presented in what may be the ideal setting for this play, Blyth’s new open-air “Harvest Stage.” (Well, new to me. It debuted in 2021 when Canada was closed to disease-bearing Americans like me.) A shallow amphitheater has been carved out of a corner of Blyth’s fairgrounds and an impressive playing area has been created out of some shipping containers, wood planks, and other construction materials. Looking semi-finished, it is itself a stage set version of a theatre and on a clear summer’s night altogether magical. It was designed by Steve Lucas, who also provided sets and lighting for the current production.

The tiered seating area accommodates 150 on surprisingly comfortable folding chairs, more comfortable than some regular theatre seats found in other area venues my wife commented. The seats are shaded and the Festival is planting a row of trees that will shield the audience from the setting sun to the left. The Harvest Stage is sure to be a permanent legacy of Garratt’s tenure as Artistic Director.

On this spacious and picture-perfect backdrop, Steve Lucas has nestled a simple farm kitchen, with a bedroom for Angus just visible up a flight of stairs, and a yard out front. Director Garratt uses every square inch of the space. A scene in which Miles attempts to learn how to drive a tractor takes place offstage right using an honest-to-God vintage tractor. Costume designer Jennifer Triemstra-Johnston has contributed farm-appropriate clothing for Morgan and Angus (they never seem to change) and perfectly ghastly but ever-so period-perfect outfits for Miles.

Another inestimable value of seeing The Drawer Boy at Blyth is that you will be in the company of audience members for whom “life on the farm” is a lived reality. Their knowing laughter clued in this clueless city boy to some of the subtleties in Healey’s script that I otherwise might have missed. Indeed it is one of the Blyth Festival’s cardinal virtues that the plays it produces speak directly to the first-hand experience of its core audience, rural Huron County.

From ripped-from-the-headlines fare like The Pigeon King and In The Wake of Wettlaufer, to tales from southwest Ontario’s legendary past like Jumbo and The Last Donnelly Standing, to light comedies about country life like Cakewalk and Bed and Breakfast, Blyth offers up plays that require no artsy-fartsy Director’s Notes to clue the audience in on their latest “transgressive” take on some dead white male’s musty play. Blyth even produced a play – created in collaboration by the cast, no less – about the history of the bar across the street from Memorial Hall on Queen Street, home to its main stage. Theatre doesn’t get any more local than that.

With the addition of the Harvest Stage, Blyth now has three performance venues, although Memorial Hall and the nearby black box studio theatre are currently closed due to Covid. It remains to be seen whether the day will come when Blyth, like its larger Festival cousins, will fill all three spaces simultaneously. I, for one, have my fingers firmly crossed. Lord knows, the energy and the talent are there.

A few logistical notes: The Harvest Stage is a fair hike along an unpaved path from the parking area and the check-in booths, although there is a drop-off area and “accessible parking” is available. (A map of the fairgrounds and a drawing of the stage are available on the Blyth Festival website.) “Sensible” shoes are advisable as is an extra jacket or shawl. Warm as these summer days can be, it gets cool once the sun has set. Seating is general admission, so early arrival is also recommended. Be sure to time your dinner reservations at the Cowbell Brewery or The Blyth Inn (a.k.a. “The Boot”) accordingly.

This is a perfect production in a perfect setting of a classic Canadian play. If you have never seen it (or even if you have) treat yourself to this very special experience. The Drawer Boy only plays through July 16, 2022, and is unlikely to transfer elsewhere. More information here.

Don’t miss another review. Follow OntarioStage on Twitter.